REMNANTS OF A MATERIAL LEGACY:

DOCUMENTING JEWISH ARCHITECTURE

AND CEMETERIES IN UKRAINE

A

visual legacy of Jewish culture, eloquent testimony to centuries of settlement, is richly

scattered throughout the Ukraine. During the summers of

1998 and

1999, researchers from the Center for Jewish Art broadened

the Center’s extensive survey and documentation work of Jewish treasures in this

country. To date, the Center has conducted eleven expeditions in the Ukraine, covering

diverse regions where architecture, cemeteries and other art objects testify to the major

presence of Jews whose lives were inextricably linked to the area.

A

visual legacy of Jewish culture, eloquent testimony to centuries of settlement, is richly

scattered throughout the Ukraine. During the summers of

1998 and

1999, researchers from the Center for Jewish Art broadened

the Center’s extensive survey and documentation work of Jewish treasures in this

country. To date, the Center has conducted eleven expeditions in the Ukraine, covering

diverse regions where architecture, cemeteries and other art objects testify to the major

presence of Jews whose lives were inextricably linked to the area.

Perhaps the richest repositories of Jewish art in the Ukraine are the hundreds of cemeteries that can be found scattered around the country. They have been the main focus of the Center’s work there. During the course of its expeditions in Ukraine, the Center has surveyed some 130 cemeteries and documented around 70 in the regions of Galicia, Volyn, Podolia and Bukovina. Some extremely rare finds have been made over the years, particularly regarding tombstones marking the beginning of Jewish settlement in the region in the early sixteenth century. More than 3,000 decorated tombstones from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries have also been found.

In 1998, the team consisting of Boris Khaimovich and Binyamin Lukin of the Center, assisted by colleagues from Lvov and the Jewish University in St. Petersburg, conducted a survey of synagogues and cemeteries in the southern Galicia region of Ukraine, and the cities and surrounding areas of Kharkov and Poltava in eastern Ukraine.

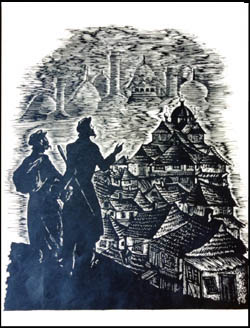

The expedition team began their journey in southern Galicia in search of cemeteries and synagogues in settlements that were set on the banks of the winding Dniester River, which flows for more than one thousand kilometers. Jewish settlement there is venerable, dating from the sixteenth century when large communities thrived in the towns and numerous shtetls sprung up on the banks and inlets of the vast river.

Starting out from Lvov, the research team’s expedition route covered the villages of Vibranovka, Novoe Strelishe, Kniaginichi, Burshtin, Bolshovtsy, Ustechko, Usece Zhelone, Belce Zlote, Chortovets, Chernelitsa and Zolotoi Potok. Some of these villages were so ‘off the beaten track’ or so close to the river that access was difficult.

| The team traveled on to Kharkov, a large industrial city in eastern Ukraine, built almost two hundred years ago. Although Jews settled in Kharkov only in the second part of the nineteenth century, they thrived as a community that numbered amongst its members a surprising number of successful architects, among them A.Ginsburg and V.Feldman. Their distinguished buildings, designed for both the Jewish and general community, helped to make Kharkov one of the most beautiful cities in Eastern Europe. |

|

By the early part of the twentieth century, Kharkov was home to five impressive

synagogues, as well as a Karaite kenasa, all of which were active until 1917. The most

lavish of them, the city’s Great Synagogue (left), was built by a Jewish architect

from St. Petersburg Jacob Gevirts, who had won the competition for the synagogue’s

design held by the community. Used as a sports hall after the Revolution, it once again

serves as the main synagogue of the Jewish community, which was revitalized after

Perestroika. Its grand domed structure was influenced by Northern European Art Nouveau

while the interior decor features Moorish elements.

Interior of the Great Synagogue in Kharkov

|

|

| The researchers found a single cemetery in the region of Poltava, located in the village of Gadiach.. A most significant grave there is that of the first Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman Mi’Lyadi, known as the ‘Alter Rebbe,’ who died in 1813. His grave is covered by a small memorial structure known as an ohel, this one resembling a small synagogue with windows. It is one of the oldest of surviving structures of this kind in the eastern Ukraine. | |

An unexpected find on this leg of the expedition: a

seventeenth century fortress synagogue still standing in the city of Khmelnik (seen

at left). Although documented in pre-war literature on synagogues in the region, this

structure, now a bathhouse in a hospital complex, was thought to have been destroyed

during World War II. Built during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the great

stone fortress synagogues served to protect the local populace–both Jewish and

non-Jewish–from attack during times of war or at the hands of marauders.

An unexpected find on this leg of the expedition: a

seventeenth century fortress synagogue still standing in the city of Khmelnik (seen

at left). Although documented in pre-war literature on synagogues in the region, this

structure, now a bathhouse in a hospital complex, was thought to have been destroyed

during World War II. Built during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the great

stone fortress synagogues served to protect the local populace–both Jewish and

non-Jewish–from attack during times of war or at the hands of marauders.

The three week expedition in 1999 covered areas in western Ukraine where researchers surveyed and documented shtetls and cemeteries in the areas of Volyn, Podolia and southern Galicia. The researchers worked in the shtetls in the vicinity of Polonnoe, one of the largest and oldest Jewish communities in the Volyn region, and in the region of Bukovina. Boris Khaimovich also led this expedition assisted by five researchers from the Jewish University in St. Petersburg including topographer and architect, Dr. Yulii Lifshits, and a photographer.

| Researchers covered more than 2,500 kilometers during three weeks of documenting during the summer of 1999. Their journey in the region of Volyn started in the city of Polonnoe, which was one of the most influential communities of that area and an acclaimed center of Hassidic learning between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. It was there that the well-known Kabbalist, Rabbi Shimshon from Ostropol, was murdered by Cossacks in 1648. Rabbi Jacob Josef wrote and published the first Hassidic book in Polonnoe, which had the first Hassidic publishing house in Eastern Europe. Today only a few remaining Jewish families are left in Polonnoe. | |

| The researchers documented the old cemetery in Polonnoe, which has 30 eighteenth century tombstones, one of the earliest, seen at left, dated 1727, and another dated 1730, above. These tombstones have finely carved borders with animal, floral and architectural motifs. The block script resembles the printing styles of the same period. |

From Polonnoe researchers traveled to Ostrog, the oldest Jewish community in Volyn, and once a very important center of Jewish learning. Many famous rabbis, like Solomon Luria (Maharshal), taught here, and was a place where some of the most famous yeshivot in Europe were established, including one founded by the Maharal of Ostrog. In this region of Volyn, Jews from Amsterdam established the first printing houses for Jewish books.

|

Three years ago the Center’s researchers documented an impressive fortress-like seventeenth century synagogue in Ostrog. Unfortunately at the time, it was used as a warehouse and the interior was difficult to photograph. When the researchers returned in 1999, they found that the building had been |

emptied, exposing the original beauty of the prayer hall, and they were able to photograph it and complete the documentation. Sadly, the enormous cemetery, which included five thousand tombstones, some as early as the fifteenth century, was destroyed in 1976. |

|

The Jewish town of Yampol in Volyn was built on an island in a lake. A single house remains which, even today, is occupied by a Jewish family.

|

The cemetery of Yampol was destroyed by the army in the 1920s and the stones were thrown into the water. Researchers were fortunate to be present when the water level was low and were able to document a few of the stones. They found about twenty tombstones from the mid-eighteenth to early nineteenth century, beautifully decorated with motifs of griffins, birds, bears, and grapes. |

One of the oldest Jewish settlements in the area, dating from the sixteenth century, was in the village of Smotrich. In the mid-eighteenth century, a wooden synagogue with rich wall paintings was built, reflecting the prosperity of the community. Suffering the fate of the vast majority of wooden synagogues in Eastern Europe, the synagogue of Smotrich was destroyed during World War II. There are no Jews left in the area today and the cemetery alone hints at the former affluence of the community.

Two areas of the Smotrich cemetery remain intact: one from the early nineteenth century, and another from the eighteenth century, the earliest tombstone dated 1723.

|

These tombstones are both from the mid-eighteenth century. Tombstones in this cemetery represent the high point of the art of tombstone carving, comprising a wide range of styles– richly carved animal and floral motifs and traditional Jewish symbols. |

In the same region, researchers documented tombstones from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, specifically in Vizhgorodok, Balin, Shatava, and in Lanovtsi, where there is a memorial next to the cemetery commemorating the 1,000 Jews who were massacred on the spot.

Several years ago, researchers from the Center for Jewish Art had documented the seventeenth century fortress synagogue in Satanov. They were very disheartened to find that, in the interim, the synagogue deteriorated significantly. There are holes in the ceiling and all the interior galleries have been destroyed. The Satanov cemetery has been vandalized and dozens of highly decorated tombstones from the late seventeenth and eighteenth century have been broken, the pieces scattered.

| Another cemetery documented by the Center for Jewish Art team was in Banilov, where the five hundred early nineteenth century tombstones offer testimony to a highly developed funerary art amongst Jews of this area. A broad spectrum of motifs were found, some similar to those in synagogue wall paintings, such as leviathans, lions, and complex geometric patterns. Traces of color on some of the stones indicate that these tombstones were once painted. The tombstone pictured here is dated 1893. |

|

Continuing into southern Galicia, researchers entered Solotvino in the Carpathian mountains, where Jews arrived in the seventeenth century. In this once large and prosperous community, the cemetery which has over 3000 tombstones, served most of the Jews in the region. The hard stone used in the tombstones has retained very clear images. The oldest tombstones are from the seventeenth century and have inscriptions resembling display script in manuscripts. The eighteenth century tombstones are typical of Galicia, with portals and triangular pediments around the inscriptions and modest adornment. The nineteenth century tombstones are decorated in a traditional local style, with lions, deer or birds holding menorahs or decorated with trees or garlands. The inscriptions are very detailed, including such information as birthplace of the deceased, why they fled their previous homes, and from which wars they had escaped. The nineteenth century synagogue in Solotvino still stands, though no Jews remain.

| Among the highlights of this expedition were the extraordinary tombstones found in the cemetery of Zolotoi Potok, a small but important mercantile center where Jews had settled in the seventeenth century. The wealth of the community is reflected in its tombstones. Many seventeenth and eighteenth century tombstones have, remarkably, remained in good condition though buried underground. The earliest one, pictured here, is dated 1633. These tombstones constitute some of the most outstanding examples of the art of tombstone | |

| carving. The

large stones, designed in Renaissance style, have large bands with grape and vine motifs.

The pediments, carved in high relief, are decorated with lions and garlands and vessels.

Fifty such tombstones were documented.

The Center for Jewish Art will continue sending expedition teams to the Ukraine. Even after many years of exploring the area, researchers are still amazed by the visual riches this region has yet to reveal. |

|

The 1999 expedition was supported by the Fanny and Leo Koerner Charitable Trust, Cambridge, Massachusetts.