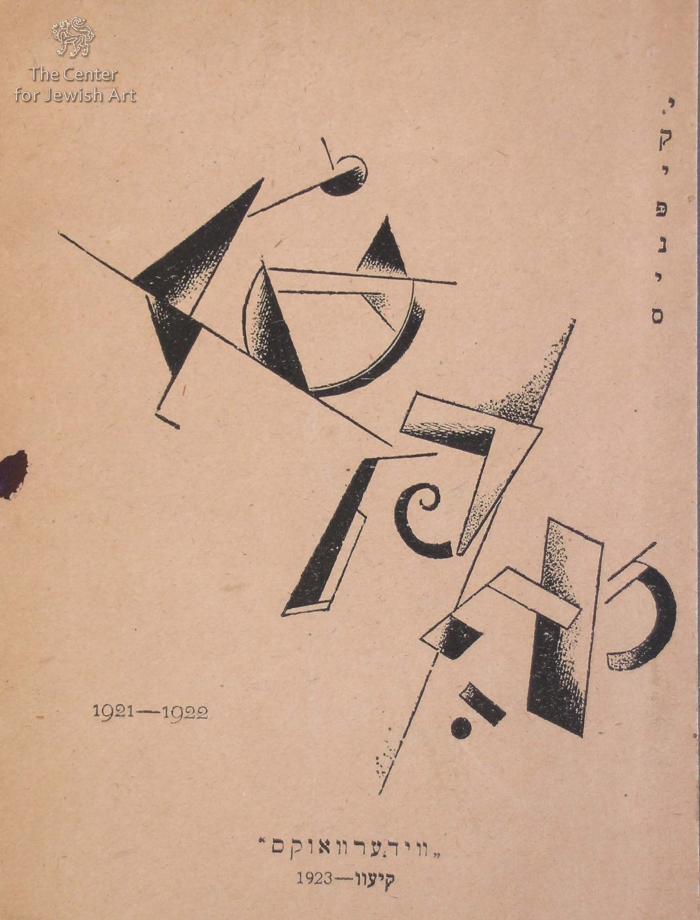

Obj. ID: 38322 Oksen (Oxen) by Y. Kipnis, Kiev, 1923

sub-set tree:

This text was prepared by William Gross:

(1896–1974), Yiddish fiction writer. Itsik Kipnis was born into a family of craftsmen in Sloveshne, Ukraine. As a child, he studied at heder and with private teachers; he later worked with his father as a tanner. In 1920, Kipnis went to study in Kiev, where he met Dovid Hofshteyn, who became his literary mentor. Kipnis’s first publications were children’s literature and a book of poems titled Oksn (Oxen; 1923) that celebrated modern, urban existence with an optimistic tone and minimalist poetic language. However, his real entry into the world of Soviet Yiddish literature was his first book of fiction, Khadoshim un teg: A khronik (Months and Days: A Chronicle), which was published with an introduction by Yitskhok Nusinov (1926).

Critics immediately recognized the book as the first significant achievement of Soviet Yiddish fiction. The first-person narrator is a young man from the shtetl Sloveshne who describes his own experience with both pogroms and revolutionary action. The book achieves a unique blend of the meaningful moments in the life of a pair of young lovers, on the one hand, and the fear and horror of murder and violence, on the other. The individual scenes have the detailed immediacy of a close-up, but the book’s composition is built on rapid transitions from one subject to another and on the alternations between refined and primitive language. Khadoshim un teg creates an atomized and fragmentary narrative world that is at once idyllic and full of horror.

The fact that Kipnis’s book about pogroms and revolutionary triumphs in the shtetl only included characters with minimal ideological consciousness placed Soviet Yiddish critics in an embarrassing position.This did not, however, hamper the critical success of the book outside the Soviet Union. Khadoshim un teg enjoyed great popularity among the Yiddish-reading public, and a Russian translation was published in 1930. Nonetheless, the book was never reprinted in the Soviet Union.

From Itsik Kipnis in Kiev to Yoysef Opatoshu and H. Leivick in New York, 18 January 1934. Kipnis reports that he has just published an article in the Soviet press criticizing his own novel, Khadoshim un teg (Months and Days), for its bourgeois and kulak nationalism. Included in the article was mention of his correspondence with "the foreign writers Opatoshu and Leivick," in which he admitted that he had relied too much on his own judgment instead of that of his "writer comrades" and "our whole proletarian organized society" when depicting the real people on which his characters were based. But he doesn't want them to get the wrong idea: Opatoshu and Leivick are held in great esteem in the USSR. He himself is involved as little as possible with politics and does not always approve of the comrades' attitude toward foreign writers, but what can he do? He is the exception and they are the rule, so he can't make too many waves. He regets the tone of his "al-khet" (conFezsion) and feels sullied by the experience. He asks them to please not judge him too harshly. In a postscript, he acknowledges that he hasn't been writing or publishing lately but says that in the near future a book of his stories, 12 Stories, will be published, as well as some children's literature. Yiddish. RG 436, Joseph Opatoshu Papers, F224. (YIVO)

During the rest of his career as a short-story writer and novelist, Kipnis generally wrote about subjects connected with his hometown, and his narratives focused on the shaping of dramatic historical events that destroyed the ostensibly idyllic nature of the past. His cast of characters includes both simple craftsmen, rooted in the rhythm of their daily life and work, and young intellectuals who, while trying to blaze a new trail, wind up not very far from the old one. The novel Di shtub (The House; 1939), which takes place in Sloveshne in the years before and during World War I and the revolution, creates a tension between the narrow world of the male craftsmen and the vague erotic and intellectual desires of the women. Even the novel Untervegns (Under Way), finished by Kipnis in 1945, is marked by a shtetl atmosphere, although its loose structure is built upon the attempts of the protagonist to discover new horizons.

At the end of the 1940s, Kipnis went back to describing his hometown in detailed memoirs, which later appeared as Mayn shtetele Sloveshne (1971). The use of a shtetl youth as first-person narrator marks a large part of Kipnis’s work. Artistically, however, he never again achieved the modernist complexity of meaning apparent in Khadoshim un teg, from the remote, naive tone of the narrator as alleged chronicler on the one hand to the drama of his material on the other.

Kipnis was very active in the field of Yiddish children’s literature and was the author of more than 30 publications in Yiddish for children and young people from the 1920s until 1940. His first children’s pieces are noted for their blend of realism and fantasy, but his work in this genre from the 1930s on was marked by the accepted Soviet rhetoric of the day. In the 1920s and 1930s, Kipnis was also a prolific translator of literature into Yiddish both for children and adults.

With the outbreak of the German–Soviet war in 1941, Kipnis was evacuated from Kiev, and did not return until 1944. Notes from his diary during that period are the core of the book Tog un tog (Day and Day), published posthumously as the fifth volume of his collected works. Kipnis strove to revive Yiddish culture in Kiev after the Holocaust, and his heightened national feelings in those years were expressed most clearly in his short story “On khokhmes, on kheshboynes” (Without Calculations; 1947). The complete version of the story was at that time printed only in the Warsaw periodical Dos naye lebn (the censored Soviet Yiddish Eynikayt published only an abridged version); in it, Kipnis expresses his wish that “all Jews” who were among the Soviet soldiers then on the streets of Berlin “should wear on their chest, along with their orders and medals, a beautiful little Star of David.” As a result of this story, a smear campaign was launched against Kipnis, a sign of the coming destruction of what remained of Soviet Yiddish culture.

In 1949, after having been expelled from the Ukrainian Writers Union, Kipnis was arrested in Kiev and exiled to camps, and remained imprisoned until 1956. Even after his release he was not permitted to resettle in Kiev, and until 1958 he was forced to live in the nearby village of Boyarka. In the last years of his life and after his death, his Geklibene verk (Collected Works) were published in five volumes (1971–1980), as were “Untervegns” un andere dertseylungen (“Under Way” and Other Short Stories; 1960); Tsum lebn: Dertseylungen (To Life: Short Stories; 1969); and Untervegns: Roman, dertseylungen, noveln (Under Way: Novel, Short Stories, N

Lissitzky, ElContentsHide

Suggested ReadingAuthor

(1890–1941), abstract artist and theorist, graphic designer, architect, typographer, photographer, and propagandist. El (Lazar [Eleazar] Markovich) Lissitzky was born in Pochinok, near Smolensk, Russia, and died in Moscow. He chose his name in imitation of El Greco and to affirm his new artistic identity. His artistic career can be divided into three overlapping periods: (1) Jewish, from 1915 to 1923; (2) Suprematist, from 1919 to the early 1920s; and (3) Stalinist, in the 1930s. The following overview emphasizes his first period, when he participated intensively in the Jewish art renaissance in Russia and played a significant role in its development (Soviet and Western critics typically discount the importance of his early work).

Shifs karta (Ship Pass), illustration from Shest’ poviestei o legkikh kontsakh (Six Stories with Easy Endings) by Ilya Ehrenburg. El Lissitzky, 1922. Collage. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem (© The Israel Museum / The Bridgeman Art Library / © 2006 Artists Rights Society [ARS], New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn)

El Lissitzky grew up partially in Vitebsk, where at age 13 he met Yehudah Pen at Pen’s art school, which Marc Chagall also attended. Refused entrance into the Academy of Art in Saint Petersburg (most likely because of the Jewish quota), in 1909 El Lissitzky entered the Darmstadt Technische Hochschule. He traveled widely in Europe, creating drawings that he later reworked. In 1914, he returned to Russia, where with the artist Yisakhar Rybak he participated in the Jewish Historical and Ethnographic Society’s expeditions in the summers of 1915 and 1916, exploring synagogues along the Dniepr River and collecting Jewish artifacts.

El Lissitzky made fine drawings of frescoes from the eighteenth-century Mohilev synagogue, which were later published with his Reminiscences (1923) in the early Jewish art journals Milgroym (Yiddish) and Rimon (Hebrew), both meaning pomegranate. These drawings were intended both to prove the existence of and to preserve Jewish folk art, as well as to provide—in imitation of the Russian Mir Iskusstva movement and cubo-futurist modernism—the basis for a modern Jewish style.

El Lissitzky’s first important work appeared in 1917, in the form of illustrations for Moyshe Broderzon’s Sikhes khulin (Profane [Idle] Chatter), a whimsical Yiddish erotic poem. Conceiving of each page as an integrated whole, El Lissitzky surrounded classic double columns of Hebrew script with stroke-based figures derived from the ornamental style of Jewish folk art. Although each leaf is different, the illustration complements the text, hastening or retarding the narrative as needed. He also added pools of saturated color over black strokes. The text was rolled like a scroll and boxed like a mezuzah. This work represents the first modern Jewish art book, fusing Hebrew scribal tradition with modernist stylized archaizing figure and line.

In 1917, El Lissitzky took part in the first exhibition of Jewish artists held in Moscow. In 1918, he joined the fine arts section of the Educational Commissariat of the Bolshevik government, illustrating Yiddish and Hebrew books for children until 1923. His drawings for Mani Leyb’s Yingl tsingl khvat (The Mischievous Boy; 1918–1919) alternated Hebrew letters with animal forms and the printed verse. This so-called Jewish style made him a much sought-after illustrator, with his work appearing in 30 different Jewish publications from 1918 to 1923.

Iz gekumen dos fayer un farbrent dem shtekn" (Then Came a Fire and Burnt the Stick). 'From Khad gadya (Kiev: Kultur-lige, 1919). El Lissitzky. Color lithograph on paper. (© 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / YIVO)

El Lissitzky’s colored lithographic volume of the traditional Passover song “Khad gadye” (One Kid; 1919)—a reworking of earlier watercolors dating from 1917–1918—marked his last innovation as a participant in the Jewish art renaissance. These 10 illustrations share a common page design, always divided into three parts. At the top is a Hebrew letter as a numeral in animal form. In the middle section there is a Jugendstil domed frame with a key Aramaic verse in Yiddish, below which is a flat, figural illustration consisting of curvilinear lines with distinct areas of color, nonrealistic scale, and an imaginative handling of pictorial space (e.g., a firebird bigger than a church; people flying about); the composition, asymmetrical and on a diagonal axis, constantly seeks to achieve a dynamic sense of movement. At the bottom of the page, one finds the original Aramaic opening words. Some see this work as supporting the Bolshevik cause in its handling of the traditional text by means of the illustrations; the color symbolism and imagery tends to support this view.

In 1919, Mark Chagall hired El Lissitzky to teach graphic arts at the Vitebsk Art Academy. With the arrival of Kasimir Malevich, El Lissitzky, influenced by the former’s suprematism, began his celebrated abstract series of drawings and lithographs, which he named Prouns (Project for the Affirmation of the New; 1919–1923). This radical aesthetic and intellectual redirection did not signal a break with his Jewish milieu, however. He relinquished Chagallian ideas of representation and the attempt to create a Jewish national style and instead embraced suprematist art as a new means of interpreting reality.

In 1919–1920, El Lissitzky participated in the art shows of Unovis (suprematist collective), producing the masterful abstract poster Klinom krasnym bei belykh (Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge), a play on the antisemitic slur “Beat the Jews!” He moved to Moscow in 1920 and joined the Institute of Artistic Culture, becoming an adherent of constructivism. In Berlin in 1922, he and the Soviet Jewish writer Ilya Ehrenburg cofounded the journal Vesh / Object / Gegenstand, devoted to constructivist issues. He also illustrated Ehrenburg’s volume Shest’ poviestei o legkikh kontsakh (Six Stories with Easy Endings; 1922). Notable is Shifs karta (Ship [Immigration] Pass) with its modernist photocollage, shaped like a Star of David and consisting of a selection from the Mishnah, a temple diagram, an American flag, a black hand pressing down, and on the palm the Hebrew letters pe and nun, the traditional po nikbar (here rests) found on Jewish tombstones. The collage suggests the end of Jewish wandering as well as the persistence of traditional Jewish beliefs.

Elefandl (The Elephant's Child), by Rudyard Kipling (Berlin: Thresholds, 1922). Illustrated by El Lissitzky. Yiddish translation of an English-language classic. (© 2006 Artists Rights Society [ARS], New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/YIVO)

El Lissitzky continued to publish on Jewish themes, contributing an article on the new art in Ringen (1922), a Polish Yiddish journal, as well as a description of the Mohilev synagogue frescoes in the journal Milgroym. Using suprematist style, he also illustrated Leyb Kvitko’s Yiddish translations of Ukrainian and White Russian folktales (1923).

El Lissitzky participated in the International Dada Congress held in D?sseldorf in 1922, published an article on his Prouns in the journal De Stijl the same year, and visited the Bauhaus in Weimar. Around this time, he designed Vladimir Mayakovsky’s volume Dlia golosa (For the Voice; 1923), using new abstract constructivist design and typography, as well as creating the design for a Proun room at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition. In 1924, he worked with Kurt Schwitters on the magazine MERZ and joined Jean Arp in creating the volume Die Kunstismen (The Isms of Art; 1925). These productive years in Berlin, when he moved in the most advanced artistic circles, were not devoid of Jewish contacts, as Berlin in the early 1920s was a center of Jewish cultural activity. A number of dadaist and Bauhaus members based in that city (e.g., Arp, L?szl? Moholy-Nagy, and Man Ray) shared the same historical roots as Ehrenburg and El Lissitzsky; all were cosmopolitan Jews or Jewish cosmopolitans.

In 1925, El Lissitzky returned to Moscow. His designs in 1926 for the Room for Constructivist Art at the International Art Show in Dresden cemented his fame as a cutting-edge artist and designer. Beginning in 1926, he produced works for Soviet trade exhibitions and propaganda shows. These included integrated display rooms that fused his interest in architecture, photomontage, photocollage, typography, and posters in the most advanced constructivist style based on his unique designs.

The absence of any Jewish connection in El Lisstzky’s life after 1926 suggests that he followed the lead of others in adapting to changing Soviet realities. Ill health led to his untimely death in 1941.Suggested Reading

Chimen Abramsky, “El Lissitzky as Jewish Illustrator and Typographer,” Studio International 172 (1966): 182–185; Alan C. Birnholz, “El Lissitzky” (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1973); Judith Glatzer Wechsler, “El Lissitzky’s ‘Interchange Stations’: The Letter and the Spirit,” in The Jew in the Text: Modernity and the Construction of Identity, ed. Linda Nochlin and Tamar Garb, pp. 187–200 (London, 1995); Sophie Lissitzky-K?ppers, El Lissitzky: Life, Letters, Texts (London, 1980); Peter Nisbet, “El Lissitzky in the Proun Years: A Study of His Work and Thought, 1917–1927” (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1995); Nancy Perloff and Brian Rich, eds., Situating El Lissitzky (Los Angeles, 2003).