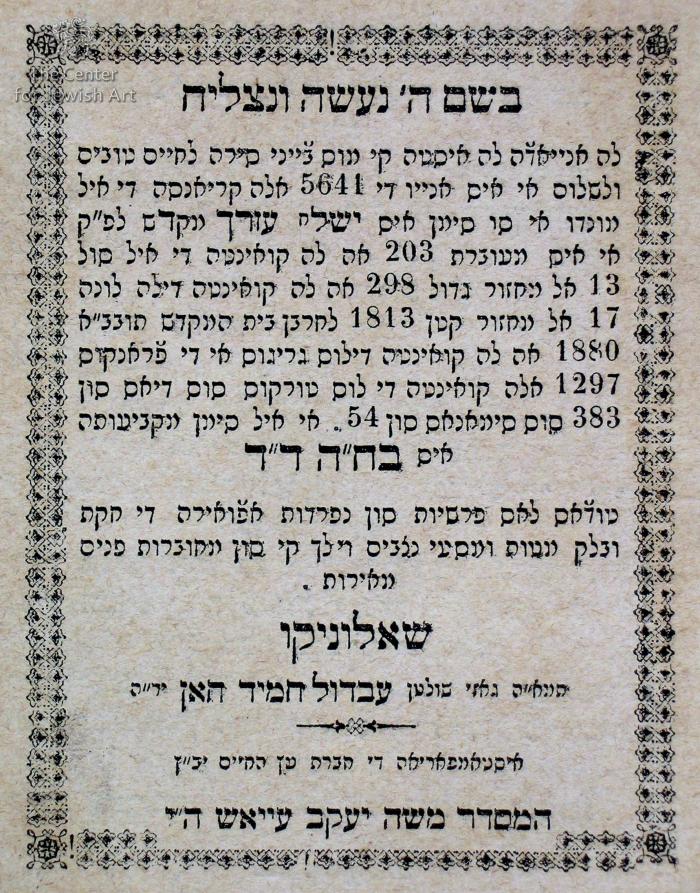

Obj. ID: 38011 Luach, Thessaloniki (Salonika), 1880

sub-set tree:

This text was prepared by William Gross:

The Hebrew or Jewish calendar (הַלּוּחַ הָעִבְרִי, ha'luach ha'ivri) is a lunisolar calendar used today predominantly for Jewish religious observances. It determines the dates for Jewish holidays and the appropriate public reading of Torah portions, yahrzeits (dates to commemorate the death of a relative), and daily Psalm readings, among many ceremonial uses. In Israel, it is used for religious purposes, provides a time frame for agriculture and is an official calendar for civil purposes, although the latter usage has been steadily declining in favor of the Gregorian calendar.

The present Hebrew calendar is the product of evolution, including a Babylonian influence. Until the Tannaitic period (approximately 10–220 CE) the calendar employed a new crescent moon, with an additional month normally added every two or three years to correct for the difference between twelve lunar months and the solar year. When to add it was based on observation of natural agriculture-related events. Through the Amoraic period (200–500 CE) and into the Geonic period, this system was gradually displaced by the mathematical rules used today. The principles and rules were fully codified by Maimonides in the Mishneh Torah in the 12th century. Maimonides' work also replaced counting "years since the destruction of the Temple" with the modern creation-era Anno Mundi.

The Hebrew lunar year is about eleven days shorter than the solar cycle and uses the 19-year Metonic cycle to bring it into line with the solar cycle, with the addition of an intercalary month every two or three years, for a total of seven times per 19 years. Even with this intercalation, the average Hebrew calendar year is longer by about 6 minutes and 40 seconds than the current mean solar year, so that every 217 years the Hebrew calendar will fall a day behind the current mean solar year; and about every 231 years it will fall a day behind the Gregorian calendar year.

The calendar is central to daily Jewish life. Events, ceremonies, rituals and prayers are all determined by the monthly lunar cycle. Therefore calendars are an essential aspect of Jewish life and have long been calculated and produced, as evidenced by the large number of Hebrew books and manuscripts dealing with this cycle and its accurate determination, as well as the number of manuscript and printed calendars that have been produced every year in both wall and booklet form. The advent of printing naturally increased both the number of calendars made and the wide-spread nature of distribution. Yearly calendars are by nature ephemera and are usually discarded after use.

In Ladino

The history of Hebrew printing in Salonica began in the early 16th and lasted some 400 years, being brought to an end only with the Nazi conquest. The first Hebrew press was established in Salonica in 1512 by a Portuguese printer and émigré, Ibn Gedalya. By the 1560’s, with the mass influx of former Marranos from the Iberian Peninsula, printing activity in Salonica reached its height, with more than 120 books published (including a few in Ladino). With the exception of a short period, however, the city did not have any well-established printing house until the end of the 17th century.

By the mid-18th century, several printing houses which were to enjoy long periods of activity had been founded. In addition to privately-owned printing houses, there were also societies which engaged in printing. The Etz Chayyim Society, which was responsible for the present volume, founded a new printing house in 1875 in competition with that of the renowned Sa’adi Halevi. Until the great fire of 1917, more than 150 books were printed there in addition to booklets, leaflets and posters. This Luach was (type) set by Moshe Ya’akov Ayash, who was himself active as a printer in Salonica. Books issued from his press are known from 1857-1858.