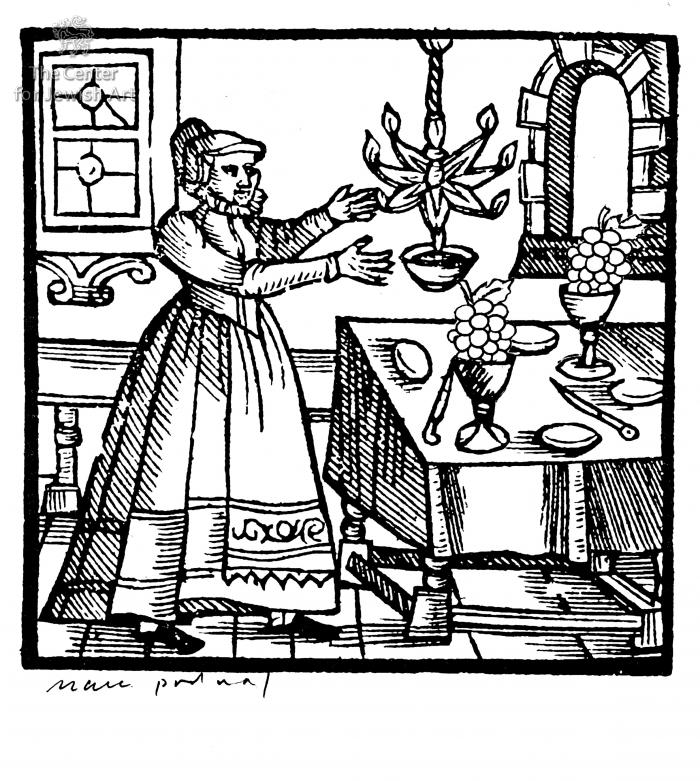

Img. ID: 400236

In "A Collage of Customs," Mark Podwal interpreted woodcuts from Sefer Minhagim (Book of Customs) published in 1593 in Venice.

Podwal writes:

"To update and introduce new layers of meaning to these centuries-old images, I’ve created a series of 26 collages. A giant electric light bulb, a microwave and a hairdryer are among the modern-day objects juxtaposed with the 16th-century depictions of Jewish customs. A comically large hamantasch (a triangular cookie eaten on the festival of Purim) collaged as Amalek’s hat pictures the ancient enemy of the Jewish people as the ancestor of the defeated villain of the biblical Book of Esther. A thought bubble inserted into a wedding illustration expresses the tradition that even at times of joy, Jews still recall the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem."

[Podwal, A Collage of Customs, 2021, p. 2]

S | Sabbath | Sabbath, Kindling the lights of

W | Woman

G | Grapes | Grapes, Cluster of

T | Table

|

Minhagim books are collections of religious practices arranged according to the order of the religious year and life cycle. When the genre first appeared in the Early Middle Ages, these volumes focused on local customs, with the purpose of ascertaining their existence and halakhic validity, and preventing them from being forgotten. Originally written in Hebrew, minhagim books were later translated into Yiddish for the benefit of women and laymen not schooled in Hebrew.

The earliest printed minhagim books were unillustrated. Around the end of the 16th century, however, woodcut illustrations were added to the text to increase the books’ visual appeal and hold the interest of the reader. The earliest printed example of such an edition was published by Giovanni di Gara in Venice in 1593.

Giovanni di Gara belonged to the Christian family that was among the leading producers of Hebrew books in Venice through the second half of the 16th century (despite the periodical bans on printing Hebrew and Yiddish books). In 1590, he printed the Minhagim book in Yiddish translation by Simon Günzburg. Originally, the book was written in Hebrew by the Austrian-Hungarian Rabbi Isaac Tyrnau (c. 1400), but it did not appear in print until 1566 in Krakow. In 1593, Giovanni di Gara printed another edition with illustrations. These woodcuts ensured the book’s fame – and popularity – and made it a model for later editions.

A large number of post-1593 printed minhagim books derive their illustrations from the Venice 1593 edition. Most examples are from Amsterdam and Germany, primarily Frankfurt am Main. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, more than 50 editions of the book were produced.