Obj. ID: 2191

Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts Munich Rashi's Commentary on the Bible, Wuerzburg, 1232/33

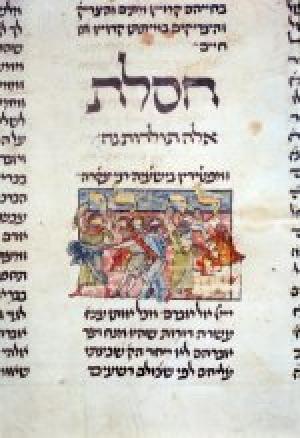

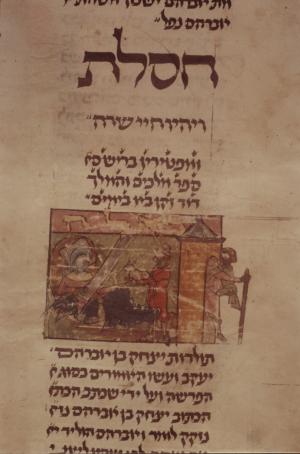

Cod. hebr. 5, originally produced as a sumptuous single volume, was divided into two around 1549 after its acquisition by Johann-Jakob Fugger (see Introduction to Fugger manuscripts). Each volume was bound by the Fugger Binder (see Binding). The lost first leaf of vol. I, as well as its last leaf were replaced, copied anew (I:1v, I:218r) by Yishai ben Yehiel and decorated by Meir. Both scribes worked for Fugger in Venice during 1549 and 1552 (see Illuminated Documents of vol. I:1v and vol. II:1r). Before the manuscript was acquired by Fugger in 1549, it was sold in Venice in 1526 by Rabbi Hiya Meir ben David to Yekutiel ben David (cf. inscription below the colophon, II:256). Rabbi Hiya Meir worked with the Venetian printer Daniel Bomberg (Amram 1909:169; Raz-Krakotzkin 2007:105), with whom Fugger had some relations (see Introduction to Fugger manuscripts). Thus it is possible that Fugger acquired this manuscript through Bomberg's printing house. It should be noted that in 1516-17 and 1524-26 Bomberg printed in Venice the first two editions of the Great Scriptures ((מקראות גדולות with Rashi's commentary, from which Yishai could have copied that for Genesis (vol. I:1v). The Style Despite the small illustrated panels, the composition is fairly spacious, even when there is a conflation of scenes, such as Abraham leaving Haran and the destruction of Sodom, Isaac blessing Esau while Jacob leaves the house, Joseph being thrown into the pit and sold to the Ishmaelites, Job with his four friends and his wife, and Nebuchadnezzar and the three Hebrews (I:9v, 21v, 34; II:183, 209). At times our artist used similar compositions where a group of people stands before an authoritative figure, either seated or standing (I:39, 44v, 63a). He also used similar postures and gestures in three other scenes where, in a group of three figures standing in a row, the first is looking ahead while the second turns to the third, all making hand gestures. The style and motifs of our manuscript show close affinities with Latin book illumination produced in Würzburg in the 13th century. This was first mentioned by H. Swarzenski (1936) and reiterated by Narkiss (1967), Engelhart (1987), Suckale (1988) and Klemm (1998, Nos. 194-195).

Fig. 3: Evangelistary Würzburg, c.1250 Munich, BSB clm 23256, fol. 1v (Engelhart 1987, fig. 11) Indeed, there are many stylistic elements which appear in our manuscript and are common to a Latin Evangelistary of c.1250 (clm 23256) and a Psalter of 1260-1265 (clm 3900), which suggest these manuscripts were produced in the same workshop. Compare for example the sitting Joseph with Augustus ordering the census (clm 23256:2; see Illuminated Document of I:39) with one hand outstretched in command and the other resting on his thigh (see also clm 3900:2v, 63; Engelhart 1987, figs. 91, 107); or the seated Moses (see Illuminated Document Documentat of I:63a) with the seated Evangelists (clm 23256:1v - fig. 3), especially Luke in the bottom right medallion (fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Luke Evangelistary Würzburg, c.1250 Munich, BSB clm 23256, fol. 1v (Engelhart 1987, fig. 11)

The faces are similarly rendered in light yellow ochre, with round eyes, arched eyebrows, a straight mouth and concave lower lip at times tinged with red (see Illuminated Documents of I:29v, I:47v; cf. clm 23256:1v - fig. 3). Another example is the profile of Jacob (see Illuminated Document of I:47v – fig. 5a) and that of the soldier (see Illuminated Document of II:209) which resemble that of Matthew in the bottom left medallion (clm 23256:1v - figs. 3, 5b): note the articulation of the hair and the upturned curl which also appear in the left-hand figure of the Psalter (clm 3900:2v; Engelhart 1987, fig. 91).

Fig. 5a: Jacob

Fig. 5b: Matthew Munich Rashi's Commentary on the Bible Evangelistary Munich, BSB Cod. hebr. 5, I:47v Würzburg, c.1250 Munich, BSB clm 23256, fol. 1v (Engelhart 1987, fig. 11)

As noted above, there are also similar motifs. The giants supporting the decorated bands in our manuscript (see Illuminated Document of I:168v) are similar to that supporting the letter P in the Evangelistary (clm 23256:3v; Engelhart 1987, fig. 167); the angel's wings are similarly rendered in both manuscripts (see Illuminated Document of I:9v; clm 23256:4; Engelhart 1987, fig. 172) and articulated in ink; and the lion at the end of Genesis (I:44) is comparable to those in the Evangelistary (clm 23256:7) and the Psalter (clm 3900:4v; Engelhart 1987, fig. 95). Despite the resemblance of both manuscripts especially in stylistic motifs, there is a difference in composition when compared with the calendar scenes of the Psalter (see Illuminated Documents of I:39 and I:63a for clm 3900:3; Engelhart 1987, figs. 89-100; chm 5, Engelhart 1987, figs. 173-174): in our manuscript the composition is more compact, the figures are mostly turning and gesturing, and the flying scrolls contribute to the movement. The colours used in our manuscript resemble those in the Evangelistary (clm 23256 – fig. 1). However, the latter's colour gradation is finer for highlights and shadows. To sum up, if a development in the style of the workshop could be sketched, it seems that the early stages are reflected in our manuscript, intermediate ones in the Evangelistary of c.1250, and still later ones in the Psalter of 1250-65 (Klemm 1998, Cat.195, p. 202). This suggestion is reinforced when the relationship between the Christian artist and the Jewish main scribe is considered. The Christian Artist and the Jewish Scribe A The iconography of most illustrated panels can be traced to Mosan art in north France and south Germany, sometimes with Byzantine antecedents such as Monreale, Palermo and St. Mark's, e.g. Noah's ark, the sacrifice of Isaac, Isaac blessing Jacob and Esau, Jacob's dream, the selling of Joseph, Pharaoh's first dream, and Job (I:6, 18v, 21v, 25v, 34, 37; II:183; Turner 1970, pp. 133-168; Frazer 1970, pp. 185-189). Exemplars with similar iconography apparently existed in the Würzburg workshop which decorated our manuscript. All the illuminated quires with panels and ends of books which were executed by the artist of the workshop were written by Scribe A: In vol. I, quires I-VI of Genesis and the beginning of Exodus (fols. 1-48v), quires IX of Exodus (fols. 63a-70v) and XXII, end of the Pentateuch and beginning of Joshua (fols. 165-172v). In vol. II the scribe had to hand two quires over to the artist: XXIV (fols. 183 Job -190; fol. 182 is an attached single leaf), and XXVII (fols. 207-212, end of Job and Daniel). All in all, the artist received from Scribe A ten of the 61 quires; the rest were partly illustrated and decorated in ink and red colour by Scribe A whenever he wrote the text. Scribe B did not decorate the text he copied, except three ends of books in ink (vol. II:121v-122; 148v-149a; 226v). In several cases the artist of the Würzburg workshop illustrated the Rashi commentary rather than the biblical text: Abraham leaving Haran and the destruction of Sodom, Jacob's dream, Jacob and Esau meeting, God reaffirms his covenant with the patriarchs, and lastly the seven-branched menorah (I:9v, 25v, 29v, 47v, 65). In two cases the panel heading one parashah illustrates Rashi's succinct reference to a story told in the previous one: the sacrifice of Isaac and Joseph meeting his father and brothers (I:18v, 44v); and in Haran and Sodom, the stories of two consecutive parashot are combined in one illustration (I:9v). It is significant to note that next to eight illustrated panels (I:9v, 13v, 21v, 29v, 34, 37; II:183, 209) there are still barely discernible inscriptions in Latin written in plummet by a 13th-century hand. There are no such inscriptions in the unpainted spaces allocated by Scribe A. Apparently these inscriptions are by the artist. Since these consist of short biblical captions and do not elaborate on the intricate iconography which was painted, it seems that Scribe A verbally explained the Rashi commentary to the painter, who noted general captions in Latin without specific iconographical details. Such co-operation, apparently in the Würzburg workshop, means that the illumination was done at the time of writing, namely in 1233, and not in the mid-13th century as suggested by scholars, when the style of the Evangelistary and Psalter reached its developed stage. It seems that our scribe did not give specific instructions about details which are common in Christian iconography, though they are also found at times in Hebrew books. One such example is Abraham and the three angels, where Michael raises his right hand in the Christian two-fingered blessing (see Illuminated Document of I:13v). Another example is God's covenant with the patriarchs, where the radical erasure of the piece of sky suggests that it included his image (see Illuminated Document I:47v). It is surprising that for the image of the seven-branched menorah (I:65) Rashi's commentary was followed for the flames bending towards the centre and the three-legged base, motifs prevalent in Jewish and Christian iconography. However, in contrast to Rashi's branches of equal height, likewise a common motif, our artist used an unusual exemplar with pairs of branches diminishing in size outwards from the central shaft, not as described in the commentary (see Illuminated Document of I:65). Later hands, presumably of owners, have scratched out the facial features of most images (Metzger 1974, pp. 549-551). Next to twelve illustrated panels (I:9v, 13v, 18v, 21v, 25v, 29v, 34, 37, 39, 40v, 63a; II:183) one hand has written in Hebrew square script the opening word of the parashot. Since the panels' original letters were distorted by the gold laid on by an artist who knew no Hebrew, and since the inscriptions were written only next to painted panels, it stands to reason that the later hand has deciphered the Hebrew opening words and rendered them legible. The patron of our manuscript, R. Joseph son of R. Moshe, commissioned another manuscript a few years after our commentary was completed, the Ambrosian Bible of 1236-1238 (see Illuminated Document of I:18v), perhaps from Würzburg. It is interesting to note that neither the iconography nor the style is comparable.

sub-set tree:

| Cod. hebr. 5/I-II (Steinschneider 1895, No. 5)

Fig. 1:

Front cover Munich Rashi's Commentary on the Bible Munich, BSB Cod. hebr. 5, vol. I

Fig. 2: Back cover Munich Rashi's Commentary on the Bible Munich, BSB Cod. hebr. 5, vol. I Both volumes have a similar binding (vol. I: 395 x 285 mm.; vol. II: 399 x 275 mm,): green morocco faded to brown on wooden boards, gold-tooled similarly on front and back with a central roundel in an undulating floral rhomboid within a large rectangle. The latter is decorated with foliate motifs at the corners and with a flower at the centre of each side of the frame (figs. 1-2). The central front roundel is inscribed פירושים (Commentaries). Above and below it is Fugger's shelf mark in Hebrew and Latin respectively: ת and Y for volume I (fig. 1), and ש (sic) and Z for volume II. The roundel on the back encloses a shield-like motif. The spine, blind-tooled with hatching has five hidden cords and head and tail bands. On the front cover are vestiges of four groups of three plaited leather bands: two on the fore-edge and one each at top and bottom, corresponding to holes from four missing nails on the edges of the back cover (see e.g. Cod. hebr. 301). The edges of leaves are goffered. The binding was done by the Fugger Binder (also called Venetian Apple Binder) in Venice in 1549 (Le Bars 2004, pp. 56-59; Hobson 1999, p. 119 and n. 65, 120-129, 255-259; Schunke 1964, pp. 173-176; figs. XVII-XIX; Tiftixoglu 2004, pp. 63, 94 and figs. 5-8; Wagner 2006, pp. 84-85). See also Introduction to Fugger manuscripts. Flyleaves: the bindings of both volumes have flyleaves torn from 13th-century German Latin manuscripts: 1. Text from a Passional: vols. I and II front pastedown and flyleaves; 2. Texts from two different Homiliary manuscripts: vol. I and II back pastedowns and flyleaves, one Homiliary for each (cf. Cod. hebr. 80, which previously belonged to Cardinal Domenico Grimani, has flyleaves similar to the back of vol. II. Indeed, its position in Fugger's Library followed our two volumes). See also History.