Obj. ID: 45421

Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts Ilan Aroch, Baghdad, circa 1800

The following description was prepared by William Gross:

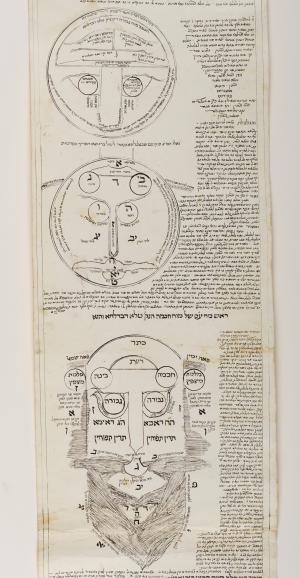

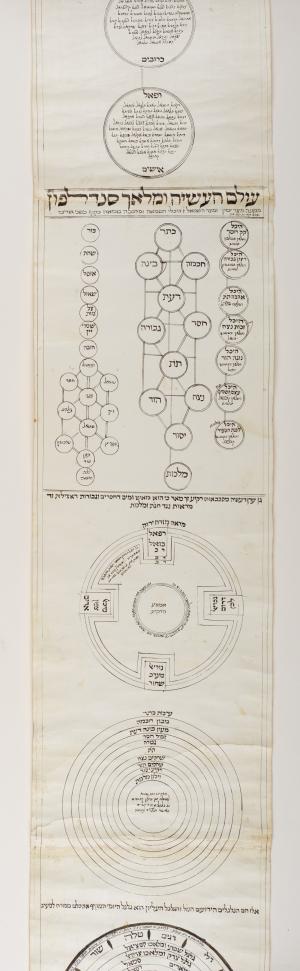

R. Sasson ben Mordechai Shantuch was a Iraqi kabbalist and Talmudist; born, 1747, he lived in Bagdad, where he died in the year 1831. In addition to Imrei Sasson, R. Sasson was the author of: Ḳol Sasson, on ethics (Leghorn, 1859; Bagdad, 1891); Dabar be-Itto, commentary on the Pentateuch and Talmud (2 vols., ib. 1862-64); Mizmor le-Asaf, on the ritual (ib. 1864); and Tehillah le-David," a commentary (ib. 1892). A large number of his manuscripts were destroyed by a fire that occurred in his house in 1853. This is the fourth manuscript from his hand in the Gross Family Collection. There is another Ilan Aroch on Parchment, some 10.5 meters in length, Gross Family Collection 028.012.009, as well a an Ilan in codex form from 1792. This example is the longest of his known Ilanot, stretching some 35 feet, the longest of his known Ilanot an perhaps the longest Ilan known at all.

This is one of only a handful of extant Ilanot created by Sasson ben Mordechai Shantuch (1747-1830), one of the most known kabbalists of Baghdad; we have evidence that his kabbalistic productivity spanned nearly half a century, from 1772-1821. Shantuch’s Ilanot were clearly intended to provide a uni# ed overview of the Lurianic theory of creation and emanation. Incorporating material from European printed works as well as from Kabbalistic scrolls from Kurdistan, Shantuch’s genius was to create a coherent work of disparate sources that spoke with one voice: his own. Shantuch’s skills as a scribal artist also lent his Ilanot a distinctive aesthetic, from the colorful title frame in this exemplar announcing it as the “Form of the Tree of Life of the Holy One Blessed be He” (Tofes ilana de-hayei liKBHu) to the unusually anthropomorphic whiskery image of “the Long Face” (Arikh anpin) at its heart. Shantuch’s Ilan is a window into the diversity of Jewish cultural life in Baghdad some two centuries ago and a testament to the creativity of its # rst known kabbalist.

Kabbalistic diagrams resembling Porphyrian trees have been known at least since the sixteenth century as “Ilanot” [Heb. pl. Arborae; sing. "Ilan"]. [First such reference known to me is in the work of Guillaume Postel, who refers to "Ilanoth" as a genre of rabbinic literature.] Ilanot constitute visual representations of kabbalistic cosmologies from the relatively simpler forms of the thirteenth century to the far more complex and ramified systems in Lurianic Kabbalah from the sixteenth century onward. The increasing complexity of cosmic trees between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries directly reflects the exponential ramification of kabbalistic theosophy that took place over those centuries. Given the overwhelmingly visio-spacial conceptions of the divine in its evolutionary “becoming” in these mystical traditions, Ilanot could serve as cosmic maps. This divine cartography aspired to capture the syncronic interrelations between the various facets of the godhead and creation as well as their diachronic, evolving emergence.

What’s an Ilan? Any synoptic diagrammatic presentation of kabbalistic cosmology. The basic graphical forms could range from the arboreal to the boldly anthropomorphic. Lurianic Ilanot, in their lengthy and complex presentations, often feature both, as well as spreadsheet-like tables. The iconic decadal tree is an Ilan, as is the intricately Baroque Hammerschlag Ilan. Diagrams expressing particular concepts within a larger framework, such as the illustrations that frequently accompany certain cosmogonic discussions in the Lurianic corpus, would doubtfully have been called ilanot by anyone. However simple or complex the pictorial-diagrammatic features of an Ilan, extensive textual material is frequently embedded in and around the geometrical forms. The texts may be paraphrastic chapter headings, original compositions, or the study notes of a student. Their connection to the pictorial features alongside which they appear is usually clear, with the text providing a verbal key to the quality or process depicted graphically. That said, in complex Ilanot, simple keying gives way to more complex and even inscrutable connections. Indeed, these manuscripts demand to be treated as “integrated systems of communication” that raise “questions about how verbal and visual patterns of meaning were constructed, combined, and modified.”

The Ilan Aroch was a pictorial scheme of kabalistic theories and structures that was prepared as a study aid by each kabbalah scholar according to his understanding. This Ilan is written by Sasson Mordechai, the greatest Iraqi kabbalist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It is written in his own hand and is one of the longest such scrolls recorded, measuring over 10 meters in length. These scrolls are filled with schematic diagrams of the ten spheres and other Kabbalistic designs. Also in the gross collection is an autograph manuscript, "Ilana Dechaya", by Sasson Mordechai, Iq.011.0018 , from 1792, which is the most comprehensive explanation existing for the structure of the Ilan Aroch. The manuscript and the Ilan are unpublished. These scrolls are quite rare. A survey has indicated that less than 150 exist in public and private collections throughout the world and examples from the early 19th century and earlier are particularly scarce. There is a second, incomplete scroll of an earlier date in the Gross Family Collection as well as a codex version almost identical to this scroll. There are several other manuscripts from his hand known in other collections.

This scroll is written on 23 sections of exceptionally fine cotton paper that are glued together.

sub-set tree:

Baumgarten, Eliezer, "Faces of God: The Ilan of Rabbi Sasson ben Mordechai Shandukh," Images 13 (2020): 91-107., https://brill.com/view/journals/ima/13/1/article-p91_6.xml (accessed November 22, 2023)